Jan Washburn, co-owner of Spann Ranch, painted “Women Are Not Livestock” in protest after the 2022 overturn of Roe v. Wade. Each summer, the sign appears along Highway 50 near Crested Butte. Photo Credit: Jan Washburn.

“The cattle buisness is a damn fine buisness for men and mules, but its hell on horses and women.”- A.L. Marriot, Hell on Horses and Women

Women’s contributions to Gunnison County’s ranching history have long been overshadowed by reductive labels such as “ranch wives,” “mothers,” or, as noted in Century in the Saddle, merely “spare cowhands.” While the roles of wives and mothers are integral and deeply meaningful, and their labor is essential to a ranch’s success and has been nothing short of essential to the success of ranches, these titles alone fail to capture the full scope of women’s labor, leadership, and influence in the ranching community. The dominant imagery of the American West- cattle barons, cowboys, and rugged individualism- has often framed ranching as a “man’s world.” Although ranching has historically been male-dominated, rural ranching communities have always relied on the labor and participation of all people involved. In turn, this dependence on the labor of all people, provided women, dependeent on circumstance, varied opporutnites to take on a wide range of responsibilities, from financial management to livestock care, often blurring the lines between gendered roles. While the contributions were long overlooked or minimized, since the 1970s and 1980s, historians and scholars have increasingly turned their attention to the archives, both written and oral, to bridge the gap

Historically, women’s work has been boxed into the domestic sphere in the history books, rarely acknowledging the many ways their labor has been indispensable—not just in the home, but in the daily operations, decision-making, and economic success of ranches and families alike. Women’s roles on the ranch have often defied traditional gender expectations, offering a space to uncover the nuances of gender dynamics. Many women have crossed figurative fenceposts—between the home and the range, between tradition and change—negotiating roles that were both expected and self-defined.

UnBranded Roles draws on the oral testimonies of women in ranching to explore how masculinity and patriarchal labor structures have shaped Western narratives—and asks: why are men nationally recognized, while women are so often overlooked? The exhibit also highlights the complexities of working within a male-dominated industry, where not all women experience gender discrimination the same way, and their perspectives on it are just as diverse. While ranching has changed over time, many of these dynamics persist today. By centering women’s voices, we can better understand how their labor has been utilized, challenged, and at times overlooked. Yet, ranching has also offered women a deep sense of purpose, pride, and opportunity—not always available elsewhere. Still, they’ve often had to work just as hard for less recognition, even as they remain hopeful and grateful for the progress made.

Below: Jeannie Miller, Barbara East, and Nola Means were interviewed at the Gunnison Library for the first interview of this project in February 2024.

Barbara East

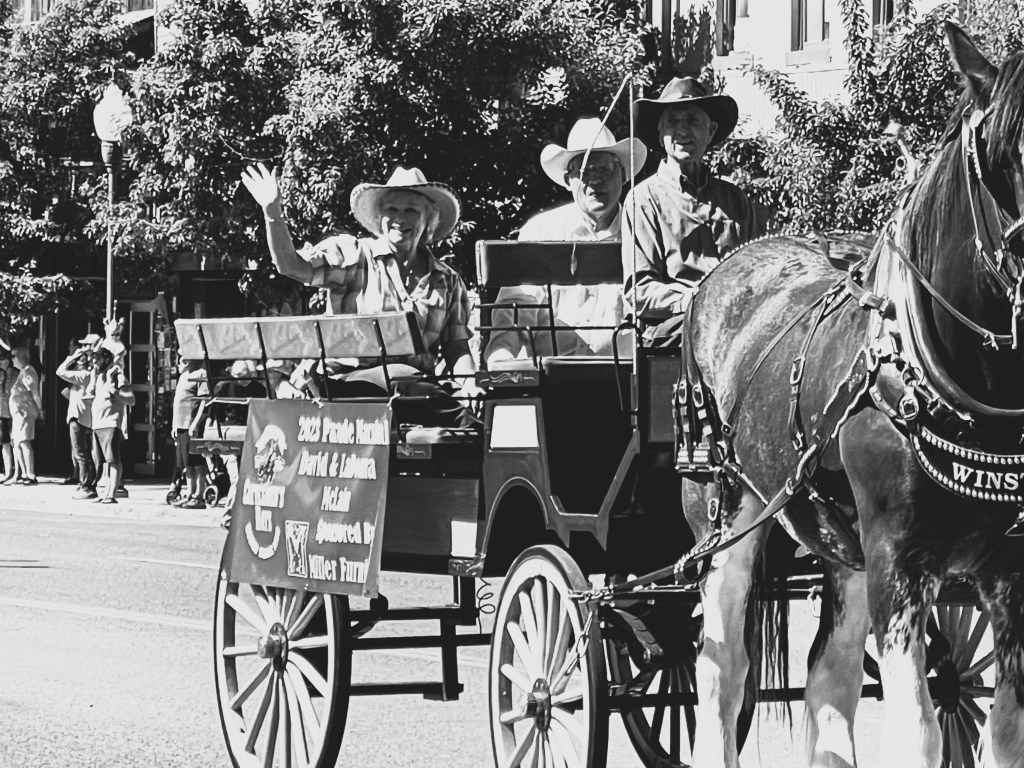

LaDonna McClain

Nola Means

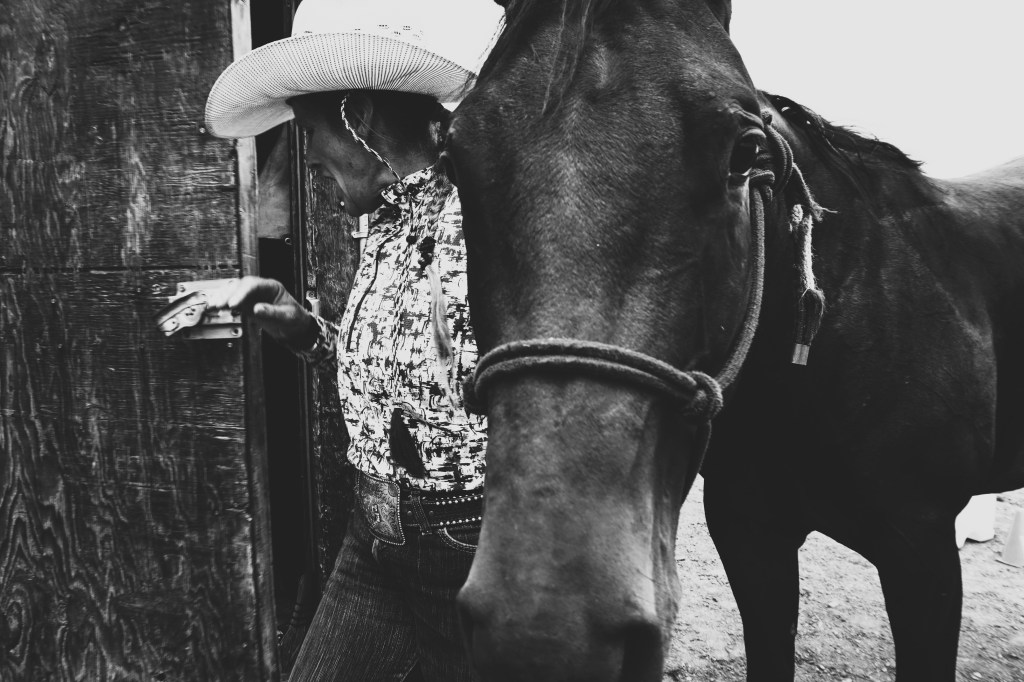

In this clip, Nola reflects on how, as she’s gotten older, she’s become smarter about her work—choosing to work the ‘alleys’ and handle cattle differently than her husband and other ranchers. She uses gentler techniques to move cattle, a practice echoed by Barbara East, who also discusses ‘low-stress livestock handling.’ Barbara also notes that you can train cattle to climb mountains, as long as you rest them, pay attention to there movements and more.

Trudy Vader

Irene Irby

Jan Washburn

Leave a comment